On the Bagratashen border after passing the Georgian-Armenian border I sat in a car to continue my journey.

“Where are you from?” the driver finally asked after looking at me long and attentively.

“Turkey,” I replied.

“Where did you say? From Turkey? Are you Turkish?” he responded without hiding his astonishment, anxiety, and aggression.

“No,” without betraying myself, “I am German by nationality…”

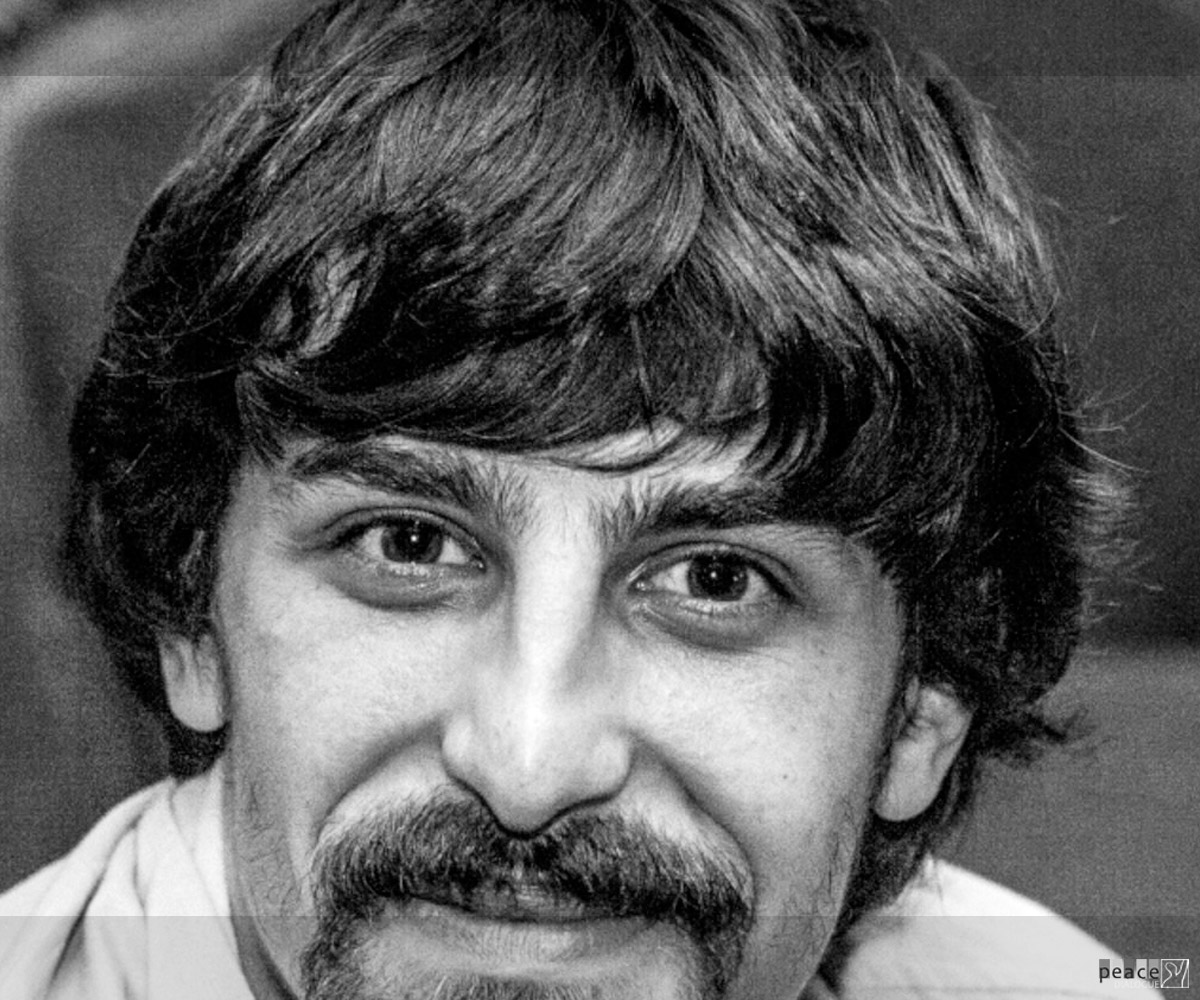

On January 22 at Peace Dialogue NGO, Onur Tahmaz, a Turkish man, told this story during an informal meeting with Vanadzorians. He continued:

After a while the driver said, “you had a long trip. You probably got tired. We should go to my place.You will rest a little bit and then continue on your way.”

Even though I travel a lot, I haven’t seen such hospitality anywhere, in any country. Onur also got to know the driver’s family. During the meal, the driver described how much he hated Turks and Muslims in general. The young Turkish man even hid his Turkish passport and all the documents revealing his nationality. In the end, after taking photographs with the hospitable hosts, he gave them a made-up German address so that there would be no doubts. Onur is going to send them their pictures and apologize for hiding the truth.

There has already been two years of cooperation between the young activist Onur Tahmaz and Peace Dialogue. The cooperation began in 2011, through Joint Civic Education, which is an initiative between the German MitOst and CRISP organizations and Iris Group, based in Georgia. The program aims to strengthen civil society representatives in the South and North Caucasus and Turkey by developing the capacities of activists in the region, especially in the field of civic education.

When visiting the region, Onur rushed to meet the Vanadzorian friends of the project. During the meeting at PD, the Turkish activist talked about his impressions and observations, the meetings held during the journey to Nagorno-Karabakh, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, and shared his concerns about the Armenian-Turkish and Armenian-Azerbaijani issues.

“When I told my Azerbaijani friends that I am leaving for Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, they were surprised at first. Then they tried to warn me that it was dangerous. Even though I was greeted with much hospitality and warmth, I still felt how stereotypes in our societies limit the chance to get to know each other.”

Onur mentioned that, understandably, Turkish media and society are more concerned with developments relating to Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenian-Azerbaijani relations than with the 1915 Genocide and the issues concerning that page of history. When reflecting about this issue, Onur and the participants of the informal meeting discussed how historical research and public sources portray this issue and to what extend that portrayal influences the public perception of the issues in the countries.

“Of course, these two issues need a quick solution but I think that the governments of those countries need to have the strength, demonstrate the civic will, and open the borders, giving the common citizens an opportunity to communicate, visit each other, and cooperate.”